Digital Privacy

Over the last few years we’ve seen a rise in personal privacy regulation. GDPR, an opt-in system for the EU came in May 2018, then in January this year was CCPA, an opt-out system only for California, and then the LGPD in Brazil, an opt-in system which became law in August. I’m sure you can see the problem here: the world is more than just Europe, California and Brazil.

On top of that we’ve seen moves from Google, Apple, and Firefox to end third party cookies in their browsers, followed by Apple pledging to require consent from users to share their Mobile App ID with developers.

Pro adtech does not mean anti-privacy.

But creepy ads still follow us around the internet and more than a few people in podcasting have concerns that adtech might have damning implications on our industry.

Podcasting stands out from all other forms of digital media specifically because of the way listeners interact with it. The RSS feed enables great reach for the podcaster and nearly limitless flexibility for the listener. Listeners can use any number of apps or websites to experience the content by requesting the episode from the hosting provider. Most of the content on podcasting costs nothing other than the sharing of session data that allows the internet to function, like IP address and user agent.

Imagine being able to watch your favorite Netflix show with your Hulu app. Or a song listed on Spotify, but with your Tidal player. It will never happen.

And yet, that’s the foundation that podcasting is built on.

The Holes in Privacy Regulation

Regulations like the GDPR or CCPA only cover some people: and there are far more areas of the world where these rules don’t apply. It’s important to keep that in mind.

If you are outside the areas covered by those regulations, declining a website’s cookie policy does nothing for you. The website will still be provided with full access to your IP address, user agent, and the content the user is interacting with. If those values sound familiar it’s because they’re the most data we get in podcasting.

For people who are covered by GDPR/CCPA it’s a little different. First, there’s a lot of debate on whether an IP address on its own is “PII” – personally identifiable information. I’m not a lawyer; and smarter people than I suggest that IP addresses on their own can be PII, but especially when combined with other data, so it’s sensible to treat IP addresses as PII in all circumstances.

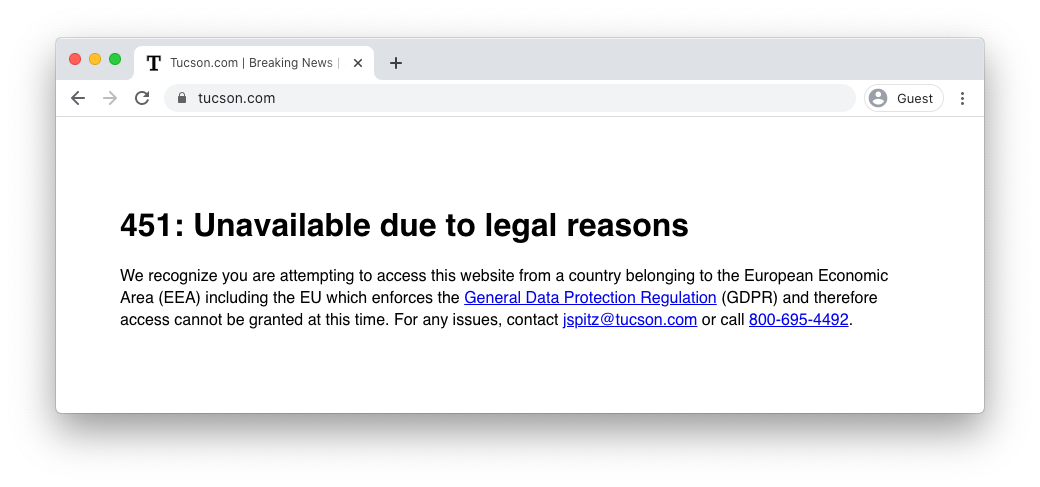

For listeners covered under GDPR – any EU citizen (including the UK) – unless they actively opt-in, using an IP address to identify anything more than their country could be illegal. In the website world, this lack of legal targeting means that many websites – like the Arizona Daily Star, for example – simply block visitors from GDPR countries. In podcasting, that doesn’t happen.

CCPA on the other hand is an opt-out platform, which currently in podcasting is pretty unfriendly for the user. Let’s say I use Spotify to listen to Fake Doctors, Real Friends by iHeart, hosted on Megaphone, and tracked by both Podtrac and Chartable. At a minimum I would have to go and visit Spotify, iHeart, and Megaphone and tell all three companies that they cannot use my personal data.

Podcast apps don’t share listener opt out data with podcast publishers.

For example – even if you opt out of Spotify using your personal data for tailored advertising – which you have to do on their website – they don’t let podcast hosting companies know that you’ve opted out. So podcast hosts will still try to serve you targeted ads, even though you told Spotify you don’t want that. (And Spotify aren’t alone here).

Who Owns The Data

There are some really important terms in GDPR and CCPA that describe how an entity interacts with data. In GDPR the terms are “controller” and “processor”. In CCPA they’re “business” and “service provider”. They mean relatively similar things, so for the sake of clarity I’ll stick with the GDPR terms.

A controller is the entity that ultimately owns the data. A processor is an entity that handles the data with permission from the controller. Every hosting provider and attribution partner I’ve interacted with in podcasting has identified themselves as a processor, which leaves the publishers of the podcasts as the “controller”, the absolute owner of that data.

Ultimately what that means is that nobody but the publisher can do anything with that data without consent. Agreements between publishers and their hosting and attribution partners provide the most limited access to that data for the processors. I can confidently say that any processor getting rights to sell the data or combine it with data from other publishers would require substantial legal work.

If the publisher, who doesn’t have direct access to the listener, is the “controller” and their hosting provider, which is one step closer to the listener, is a “processor”, where do the podcast players (the apps used by listeners to subscribe and/or listen to an episode of the podcast) fit in?

Podcast Players Hold All the Power

Did you know that there are no privacy standards associated with podcast players? These apps, which anyone can make, only exist because of the open content of podcast publishers. Yet they don’t have to share any data with the hosts or publishers.

Spotify is a great example. It’s a platform whose content includes podcasting. It’s a data rich, sign-in-required walled garden, just like Facebook. It serves ads in real time like streaming services such as Pandora. While they do serve ads to people who listen to podcasts, Spotify is not offering podcast advertising. Spotify is offering in-app advertising, and app advertising heavily utilizes PII — really personally identifiable information pulled from the profiles users create, including all of the actions taken by a user inside the app. Why wouldn’t they? Spotify’s listeners gave Spotify the right to use their personal data.

It’s easy to make an argument that podcasting wouldn’t be where it is today without the podcast players. But would the podcast players even exist without the publishers? Did Serial make Apple Podcasts popular or did the availability of Apple Podcasts allow for Serial’s success?

But do the apps identify as data “controllers”? Clearly, apps are not joint controllers with the publisher because apps don’t share all the data collected with the publishers. I suspect Spotify views themselves as a controller, but not every small app would want to take on that responsibility.

Let me be clear: every podcast app, big or small, knows much more about the listeners than any podcast publisher does.

All FUD, No Solutions

Everyone is talking about podcast privacy lately. Some of the articles I’ve seen provide a really great overview but no suggestion on a solution. Others are confusingly written by ad agencies who apparently want to tell everyone reading Tech Crunch that this space is a mess (in two parts).

But behind all that mainstream overview of the issue, there are some within the podcasting space being unnecessarily alarmist.

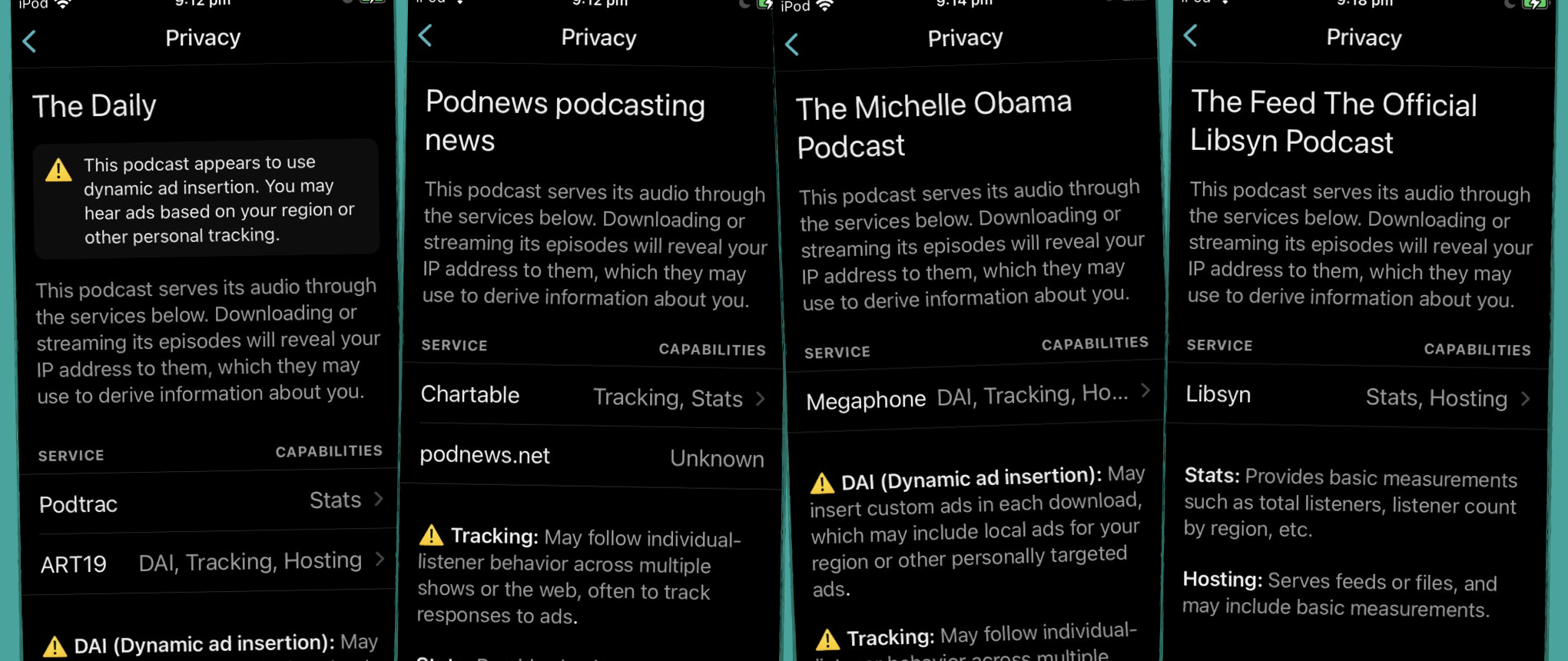

Overcast is a popular, iOS only, privacy-aware podcast app that recently released a new feature that shows you a privacy screen for each podcast.

On the privacy screen screen, it shows you all the services the app can detect that the show you’re listening to is using. Stats and hosting are displayed with no indicator, but you’ll notice that tracking and DAI have big caution signs next to them. Listeners can’t take any action to opt-out of this behaviour, so most will simply ignore it – and this might desensitize them for next time.

On the surface this looks really cool, but when you peel it back it’s not quite as cool as you’d think. Is it bad that the publisher of this podcast is ensuring the ads you hear will be less irrelevant and the product is at least available in your country? Does NPR’s Consider This, which uses dynamic content insertion to insert local news stories into a podcast, need a “warning”? Or is it actually a feature?

Developer Marco Arment doesn’t list anywhere how he identifies what hosts should have DAI listed next to them. And whatever list he’s using, it’s inaccurate. The most blatant example of this is Libsyn, a podcast host that says it offers DAI (“ad stitching tools that inject ads in your episodes targeting specific geographic regions for custom delivery”), but lacks a “warning” identifier on Overcast.

EDIT May 2021 – Overcast has now updated their records to reflect that Libsyn offers DAI.

That’s curious: because Rob Walch, VP of Podcaster Relations at Libsyn, has aggressively used screenshots of Overcast’s privacy page more than a dozen times to try and shame podcasters on Twitter for using service providers that offer tracking or DAI features. Several of those tweets were aimed at former Libsyn customers that have migrated to other hosting providers.

The fear campaign doesn’t stop there. Rob Walch was also a guest on the (Libsyn-hosted) podcast In A Few Minutes back in September, talking about tracking and privacy, and made the following point:

“What about an LGBTQ podcast and you travel to Dubai and you step off the plane with your partner and someone’s following you because you were in a database having listened to multiple LGBTQ podcasts?”

Rob got the important bit right: this is terrifying, since the UAE is one of the countries where homosexuality is illegal. But what he got wrong is how this could be tracked. Yes, you could combine IP data with other signals through the third-party services Libsyn support to potentially be able to discover a person’s name and address, though as we’ve seen above it’s hard to do so and the data is unlikely to be available to authorities. But the real risk for the individual he described is listening to a podcast hosted by Libsyn.

LibsynPro publishes both secure (HTTPS) and unsecure (HTTP) RSS feeds for all their customers. Libsyn’s support documentation gives examples of entering the unsecure HTTP version of their RSS feed, rather than the secure HTTPS version that Apple Podcasts “strongly encourages”.

In my tests, many shows hosted on Libsyn Pro with adult content, like Friday’s, or Stories from the Street, will – in the Apple Podcasts app or in Apple’s Safari browser – play from an unsecure URL: and will advertise that fact to anyone who cares to monitor your internet traffic. (Chrome, incidentally, switches it to the secure version).

So, when you use unsecure HTTP then everyone who can see your internet traffic can also see what RSS feeds you’ve requested, or what audio you’re listening to. Who do I mean by “everyone”? Anyone: your workmates, your employer, your internet service provider, or even the government.

When that user in Dubai requests an LGBTQ+ podcast hosted on LibsynPro, it’s not adtech that could get the listener arrested: it’s the unsecure Libsyn URL that their internet service provider can openly read, identify the show, and forward the information to the police.

It’s 2020. You don’t get credit for pointing at a problem and yelling that it’s wrong, especially when you’re in a position capable of effecting change.

The Solution To All This

Imagine if all the major podcast publishers or hosting platforms got together and defined very straightforward obligations (not best practices) for privacy that podcast players had to follow to get access to their content. I don’t think apps like Spotify, Apple, Google, and Amazon would tell their users that they can’t access NPR or Crooked Media because the apps refuse to tell the publishers if the listener has opted out of tracking.

We need a consent framework in podcasting. A uniform way for apps to pass signals down to hosts and service providers, notifying them of user preferences. This progress has been blocked by the lack of communication between publishers and hosts. Outside of the IAB’s focus on download reporting for the hosting companies, there’s no collaboration. Each company views themselves as an island, unwilling to collaborate with their perceived competitors.

After spending 50+ hours in the last 30 days talking to amazing and highly intelligent people in the podcasting space, I can confidently say that everyone wants to collaborate on this. They just don’t all have permission to do so.

As a pro adtech independent in the podcasting space, I would like to use my neutrality to help organize this solution. Let’s come together and build this consent framework.

If you’re interested, please reach out to me directly. I truly hope Rob and Marco are the first to join.

No Homework This Week

Instead of homework this week, I want to use this space to remind everyone that I specifically started writing Sounds Profitable so I could talk to everyone in podcasting and bridge gaps between companies. My goal is to improve this space for everyone. I’ve had nothing but amazing conversations with highly educated and opinionated people at many different companies. They all express the same desire to talk about these topics and collaborate with others on a resolution, but their companies see each other as competitive.

You’ll find going forward that I’m unlikely to quote people or reference companies. It’s become abundantly clear that I’ll be able to learn about and discuss far more important issues if I don’t have to ask everyone to run their comments by their PR department.

I appreciate your support of Sounds Profitable and I am truly excited to continue to deep dive into tough topics and collaborate with you on solutions.

Please consider sponsoring Sounds Profitable or reaching out to me directly to discuss ideas for how we can collaborate to make this space better.

New Sponsors!

It’s our goal to highlight the amazing people and companies that are helping Sounds Profitable grow.

This week marks our sixth newsletter, and we’d like to personally thank our latest sponsor: NPR, a daily source of unbiased independent news and inspiring insights on life and the arts.

I have worked with NPR in some capacity nearly my entire career and I am over the moon to have their support in continuing Sounds Profitable.