Hosting companies were designed for podcasters, not podcast agencies or production houses. So Fatima Zaidi, founder and CEO of Quill, decided to build one that was. Listen in as she and Bryan talk about their new platform, Co-Host

Tom writes…

So, big shocker–I am going to talk about research today. I know, WHO WOULD HAVE THOUGHT. But I want to talk about it a little differently this month, especially as Sounds Profitable moves forward with its big hairy audacious goal to make podcasting better for everyone. Part of that is not just making research better, but also making everyone in the space better consumers of data.

In my 18 years at Edison, I have pretty much only talked about Edison-produced studies. Besides the fact that it wasn’t my job to talk about what other research companies were doing, I also didn’t want to be perceived as biased. So, unless I thought something was particularly good, or powerful, I generally haven’t talked much about it.

But any day now, the gloves are off, baby. Prepare for a withering torrent of criticism!

Just kidding. But I did want to write about some of the recent studies that have come out about podcasting – not specifically in the way Caila excellently writes for Good Data (found monthly in this space), but in broader terms that I hope will drive the industry forward.

A lot of the data you’ve seen over the past month seemingly doesn’t jibe with other data you may have seen. In some cases, you may have even seen data that contradicts data from the same company! I am not going to pull out any negative examples here. I just had my second COVID booster yesterday and I am in too fantastic a mood to poop on anyone’s research. Because the truth is, almost every research study you have seen about podcasting has some merit to it.

Here’s the thing: there is no such thing as a perfect study. There, I said it. Any form of research has its flaws (really, any form of data, period.) But I want to know those flaws up front, so I can tell the best story about that data. When I review a study about podcasting, I don’t look at it skeptically, and certainly not cynically. I do, however, look at it critically. And not only do I want you to do the same, I want the companies who produce and sponsor these studies to make it easier for us to do so.

So if I had one wish this holiday season May, it would be for the companies who are putting out podcast research to tell us exactly how you got the data. That’s it. The first thing I look for whenever I look at a new study is the methodology statement. It’s not to find fault with the study–it’s just to understand how they got the results they got. If two companies put out wildly different numbers for what seems like the same thing, chances are they each approached it differently. Knowing exactly how they conducted the research lets me, in turn, use both studies to triangulate the truth and put the insights into context.

Here are some of my pet peeves. I am eager to cover all the research in the space, but I’m not going to give a lot of air to studies that violate one or more of these really simple points. It is my hope that any company putting out research makes this information clear and readily available–and for those writing about these studies, make sure these questions are answered to your satisfaction first. That’s the way we will all get the best data to move the space forward.

What actually is the source?

This is not as straightforward as it sounds. Before you can even get to how the study was done, you need to find the actual source of the study. Often you will only find the methodology of the study where the original report was published. Here are two constructions of this that make me stabby:

Acme Company Podcast Report – Source: Acme Company [no methodology listed]

This construction is essentially how my high school French teacher used to respond when we would ask her why we had to do something: “Parce’que Je le dit,” which means “because I said so.” This kind of credit tells you to look at the same graph, but you know, harder next time.

But even worse is this one:

Acme Company Study A – Source: Acme Company Study B

Acme Company Study B – [no methodology listed]

Now you just ticked me off, because you didn’t print a methodology after all but you GOT MY HOPES UP.

How many humans did you talk to, and when?

Most studies are pretty good about reporting the sample size. I am often asked what the “ideal” sample size is, but it really depends on the population you are sampling. If you are sampling “Americans 18+,” you’d best be well into the high hundreds or the thousands, before the margin of error for that data settles down a bit. But a study of the “Top 100 podcasters?” I mean, I’d be good with 25.

One thing to be careful of is “global studies.” I did see one study recently that made some claims about podcast listening from a sample of 300 people–ok, fine–in 10 different countries. This is not a study of 300 people. It’s 10 studies of 30 people. Trust me, no one in podcasting–yet–can afford a truly global study.

Just as important as sample size is the sample frame–i.e., the period of time over which the data were collected. A study of the popularity of Christmas Music will look very different collected in November than it would in February, which is a fairly obvious example, but sample frame has subtle effects on any data. The exact dates are key–I like to know the time span it took to collect.

If you put the methodology behind a registration gate or a paywall, rest assured I will never register, which means I will never write about your study, and I know this headline is not in the form of a question and is kind of long but I’m just telling you.

That’s all I have to say about that.

How did you get the data?

The bread and butter sampling method for most research companies today is a large online panel that is carefully maintained to make sure it is weighted to the US online population, protected against people who take surveys every day, and continually “weeded” for bad apples. They aren’t perfect, and they have a couple of distinct biases, but those biases are predictable. If a study says that it uses such a panel, it generally can fairly say that it is representative of the online population, which in podcasting is what we care about.

A “panel” consisting of a company’s customer database, or people who responded to your email, or people who clicked on a Twitter link, can make none of those claims. This doesn’t make them useless (I mean, they aren’t great–especially not the Twitter link kind–but they aren’t useless.) It just helps to know how, so you can contextualize things.

I have a friend who is crazy into crypto and NFTs, and they tweet a lot about those topics. They are also fond of running Twitter polls, and posting the results as “research.” What they are is reflective of people who follow this person, and not much else. But show me two polls with the same question from the same Twitter account taken six months apart? Well, you can tell a story about that.

Does it do what it says on the tin?

I am an incurable Anglophile, and this is one of my favorite advertising slogans from the UK. Simply, if the bottle says “gets whites whiter” or “tastes like homemade,” it should, in fact, do that.

This relates directly to the previous point. If a study of podcast listeners is based on anything else but a representative stratified online panel or a phone survey, it certainly has value, but it cannot say “According to the Acme Poll, 56% of podcast listeners enjoy lima beans.” First–it isn’t true, and you haven’t eaten these in your life. Second, you can’t characterize the sample as “podcast listeners” because most podcast listeners couldn’t possibly take the poll, and you don’t know anything about the ones that couldn’t. The best you can do here is simply say exactly how you did get your sample, and say “According to the podcast listeners we surveyed…” or “56% of respondents to the Acme Poll said…”

The only way to claim that a study is representative of podcast listeners in general is if the respondents were randomly sampled from a panel or universe that is, itself, representative of the US population. That’s pretty simple. I just want to know how you got the sample and I promise I will find the value there.

This is less about how the data is collected, and more about how it is reported. People who write headlines love to make grand statements. “80% of Marketers love Twitter” sounds a whole lot clickier than “80% of Marketers who responded to our Twitter poll love Twitter.”

While this sort of thing generally happens with people who write about these studies after the fact, sometimes the authors of a study make these simple but false claims because it sounds better. If you are ashamed to print exactly how you collected the data, maybe don’t collect it that way. Otherwise, please just say what you did.

If your sample is 83 people, please don’t report results to a tenth of a percentage point

I mean, really think that one through.

Pay close attention to data sources in infographics

Often, those data are pulled from multiple sources, which means multiple methodologies. Doesn’t make them wrong, but it does mean that you can’t necessarily process those studies with the same lens. Putting ‘em on the same shiny page don’t make it right. And now I’ll be on my way.

Wrapping Up

Beyond this, I suppose I could talk about weighting data or a statement of limitations or even a disclosure about how sample quality is monitored, but my intent here is not to give a statistics lecture–it’s to plead with companies producing these studies, and the people writing about these studies, to answer a few simple questions about where the data came from and how, and to disclose that fully and clearly. That’s it. I am not intending to slam research in this space that isn’t transparent about these things. I just won’t write about those studies. I want to write about those studies.

The more transparency we have in this business, the more actual decision support podcasters have, and the more accurately they can judge the risk/reward ratio of what they are doing. Every time a podcaster makes a bad decision based on a poorly disclosed or reported study, a unicorn gores a puppy. Save the puppies.

Rel’s Recs

Arielle Nissenblatt of EarBuds Podcast Collective this week has chosen My Unsung Hero from Hidden Brain, hosted by Simplecast.

I came across My Unsung Hero when my podcast (and real-life) friend, Lauren Passell, shared an episode that she told a story on this past week. I’d previously heard the story Lauren shared in real life so it was very interesting to see how Hidden Brain shaped it and brought it to life in podcast form. And it was such a trip to hear Shankar Vedantam talk about my friend AND give her newsletter a shoutout. Lauren slipped on ice and broke her hip seven years ago, and a complete stranger saved her.

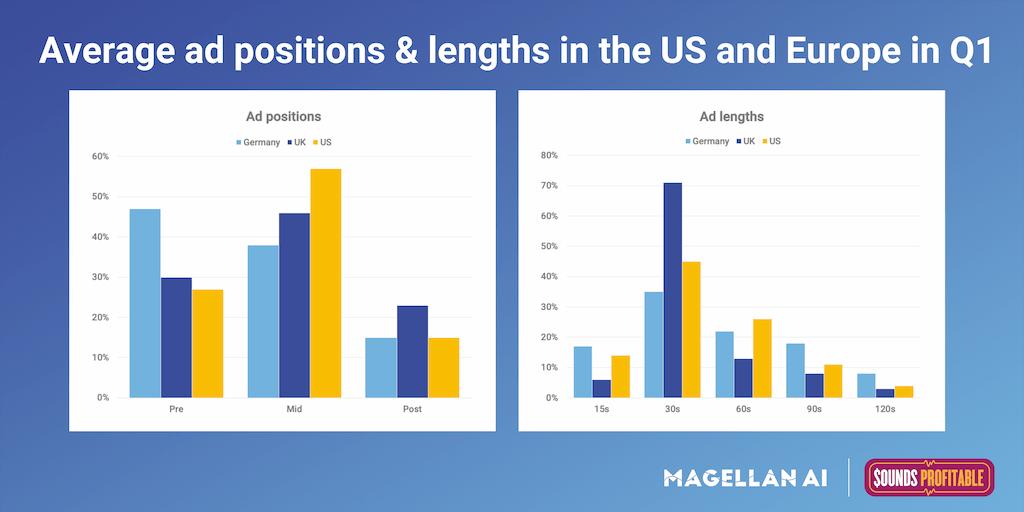

Market Insights with Magellan AI

This week we dug into the most popular ad positions and lengths on podcasts sampled in Germany, UK, and US. We like this metric because it speaks to some of the differences that exist in the podcast market across various countries.

In our analysis, we found that in Germany the most popular ads were 30s Pre-Rolls, and in the UK and the most popular ads were 30s Mid-Rolls. We found it noteworthy that in the UK 30s ads are by far the most popular, making up over 70% of the ads analyzed. By contrast in the US, 30s ads made up less than 50% of the ads analyzed with 60s ads accounting for 25% of the ads.

Interested in more insights like this? Download the Q1’22 Podcast Advertising Benchmark Report for a full analysis of the US.

Anatomy of an Ad with ThoughtLeaders

Sponsoring brand: Magic Mind

Where we caught the ad: You Made it Weird with Pete Holmes

Who else has sponsored this podcast? MeUndies, Everlane, Ritual, and Harry’s

Where else has this brand appeared? Sleep and Relax ASMR, Brand Your Power, and Project Management Podcast

Why it works: Pete Holmes hooked listeners into the Magic Mind ad read by banging the product on the table – what a way to get listeners’ attention. This ad-read was seamlessly baked into the podcast, highlighted all the brand and products’ relevant information in a genuine manner, and was honestly fun to listen to. Not to mention a killer offer. What more could you ask for from a podcast brand sponsorship?

Check out all the in-depth Anatomy of an Ad from ThoughtLeaders!